Understanding DEMPE Functions – Intangible Asset Allocation and Transfer Pricing Compliance

- Blog|Transfer Pricing|

- 14 Min Read

- By Taxmann

- |

- Last Updated on 30 August, 2024

DEMPE functions refer to the Development, Enhancement, Maintenance, Protection, and Exploitation of intangibles within multinational enterprises (MNEs). These functions are critical in determining the economic ownership and the allocation of returns from intangible assets like patents, trademarks, or technology among related parties within an MNE. The DEMPE framework, outlined by the OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines, requires that entities performing these functions and bearing associated risks are compensated at arm's length, reflecting their contributions to the value of the intangibles. This approach ensures that returns from intangible assets are aligned with the actual economic activities, risks, and contributions of the entities involved, rather than merely their legal ownership.

Checkout Taxmann's BEPS Implications on Transfer Pricing | Indian Perspective which is a comprehensive guide to understanding the transfer pricing implications of the BEPS project in India, resulting from two years of extensive research by transfer pricing experts. It covers many topics, including an overview of BEPS objectives, international rulings, and their implications for transfer pricing. Key features include insights into Indian law, planning for intangibles, economic ownership, substance in transfer pricing, and benchmarking financial transactions.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

Although the legal owner of an intangible may receive the proceeds from exploitation of the intangible, other members of the legal owner’s MNE group may have performed functions, used assets, or assumed risks that have contributed to the value of the intangible. Members of the MNE group performing such functions, using such assets, and assuming such risks must be compensated for their contributions under the arm’s length principle. Ownership of intangibles as per Development, Enhancement, Maintenance, Protection and Exploitation of intangibles (“DEMPE”) confirms that the ultimate allocation of the returns derived by the MNE group from the exploitation of intangibles, and the ultimate allocation of costs and other burdens related to intangibles among members of the MNE group, is according to the principles described in Chapters I-III of the OECD TP Guidelines, 2022 (hereinafter referred to as ‘Guidelines’).

The framework for analysing transactions involving intangibles between associated enterprises requires taking the following steps:

- Step 1: Identification of economically significant risks in relation to a particular transaction (basis of likelihood and size of the potential profits or losses arising from the risk)

- Step 2: Analysing contractual arrangement to determine the assumption of economically significant risks in relation to a transaction

- Step 3: Undertaking functional analysis to determine actual conduct of the AEs in relation to the assumption and management of risks in relation to a transaction

- Step 4: Confirm consistency between contractual arrangements and conduct on ground (as seen from step 2 and 3)

- Step 5: Guidance on allocating risks amongst parties to the transaction, in case, the parties identified in the steps above do not control such risks or do not have the financial capacity to assume such risks

- Step 6: Determination of arm’s length price based on financial and other consequences of risk assumption as documented and understood between points 1 to 5 above

The above steps are discussed in detail below:

1.1 Identify the intangibles and risks

The OECD states that MNEs should start their analysis by identifying the intangibles used or transferred in the transaction. This should be done “with specificity”, as applying too broad or narrow a definition of ‘intangible’ could result in an inaccurate compensation delineation.

For the purposes of the Guidelines, ‘intangible’ refers to something that is “not a physical asset or financial asset, which is capable of being owned or controlled for use in commercial activities, and whose use or transfer would be compensated had it occurred in a transaction between independent parties in comparable circumstances1.”

Section A of Chapter VI of the Guidelines provides guidance on identifying risks associated with intangibles for the purposes of transfer pricing. This step involves identifying the “specific, economically significant risks” associated with DEMPE in the transaction.

Here expounds upon the various facets of “risk” that are dealt with in transfer pricing analysis:

Assumption and Allocation of risks

- Control & Authority

-

- Decision to accept risk bearing opportunities;

- Decision to respond to risks, and

- Performance of actual functions

- Risk Management Function

-

- Decision to accept risk bearing opportunities;

- Decision to respond to risks; and

- The capability to mitigate risks

- Financial & Technical Capability: This includes the access to funding to take on or lay off a risk, pay for risk mitigation functions and bear the consequences if the risk materializes

There are many definitions of risk, but in a transfer pricing context it is appropriate to consider risk as the effect of uncertainty on the objectives of the business. In all of a company’s operations, every step taken to exploit opportunities, every time a company spends money or generates income, uncertainty exists, and risk is assumed.

Risk is associated with opportunities and does not have downside connotations alone; it is inherent in commercial activity, and companies choose which risks they wish to assume in order to have the opportunity to generate profits. No profit seeking business takes on risk associated with commercial opportunities without expecting a positive return. Downside impact of risk occurs when the anticipated favourable outcomes fail to materialise.

The significance of a risk depends on the likelihood of the risk and its size. The arm’s length principle of the potential profits or losses arising from the risk. For example, a different flavour of ice cream may not be the company’s sole product, the costs of developing, introducing, and marketing the product may have been marginal, the success or failure of the product may not create significant reputational risks so long as business management protocols are followed, and decision-making may have been effected by delegation to local or regional management who can provide knowledge of local tastes. However, groundbreaking technology or an innovative healthcare treatment may represent the sole or major product, involve significant strategic decisions at different stages, require substantial investment costs, create significant opportunities to make or break reputation, and require centralised management that would be of keen interest to shareholders and other stakeholders.

Risks can be categorised in various ways, but a relevant framework in a transfer pricing analysis is to consider the sources of uncertainty which give rise to risk.

The following list of transfer pricing risks, not hierarchical, emphasizes considering various risks from associated enterprises, whether internally or externally driven, for a comprehensive analysis. Specificity in identifying material risks is crucial.

- Strategic risks or marketplace risks: External risks, stemming from economic, political, regulatory, competition, technological, and social changes, can impact a company’s product focus, market choices, and resource investments. While these uncertainties pose potential downsides, correctly identifying and addressing them can lead to substantial upsides, securing a competitive advantage. Examples include market trends, entering new geographical markets, and concentrated development investments.

- Infrastructure or operational risks: Business execution uncertainties, such as operational effectiveness and process efficiency, can significantly impact a company’s reputation and existence. Successful management enhances reputation, while failures like delays or quality issues can affect competitiveness. Infrastructure risks, externally or internally driven, encompass factors like transport, political situations, laws, employee capabilities, and IT systems.

- Financial risks: All risks are likely to affect a company’s financial performance, but there are specific financial risks related to the company’s ability to manage liquidity and cash flow, financial capacity, and creditworthiness. The uncertainty can be externally driven, for example by economic shock or credit crisis, but can also be internally driven through controls, investment decisions, credit terms, and through outcomes of infrastructure or operational risks.

- Transactional risks: These are likely to include pricing and payment terms in a commercial transaction for the supply of goods, property, or services.

- Hazard risks: These are likely to include adverse external events that may cause damages or losses, including accidents and natural disasters. Such risks can often be mitigated through insurance, but insurance may not cover all the potential loss, particularly where there are significant impacts on operations or reputation.

Analyzing the economic impact of risk on pricing between associated enterprises is crucial in the broader evaluation of how value is created within a multinational group.

Decision-making regarding risk control is distributed among various levels within the multinational group, from board and executive committees setting overall risk levels to line management addressing day-to-day operational risks. The focus is on aligning risk management with commercial objectives and achieving anticipated returns2.

1.2 Identify the contractual agreements

The second step of the OECD’s analysis framework is to identify the contractual agreements relating to the transaction. Written contracts for controlled transactions “reflect the intention of the parties at the time of the contract, including […] the division of responsibilities, obligations and rights, assumption of identified risks, and pricing arrangements.”2a At this stage, MNEs should place “special emphasis on determining legal ownership of intangibles based on the terms and conditions of legal arrangements3”. This includes registrations, license agreements and other contracts that indicate the legal ownership of intangibles, and rights and obligations in a transaction.

It is important to note that the determination of legal ownership, by itself, does not influence remuneration under the arm’s length principle. Compensation is dependent on the DEMPE functions performed, assets used and risks assumed by MNE entities in relation to a transaction involving intangibles4.

1.3 Identify which parties performed DEMPE Functions (Actual Conduct)

DEMPE Functions

- Development of intangible asset

- Enhancing value of intangible asset

- Maintenance of intangible asset

- Protection of Intangible asset against infringement

- Exploitation of intangible asset

DEMPE roles could be dispersed and operate virtually impacting the sustainability of the IP model

By means of FAR analysis, MNEs must identify which parties performed functions, used assets and managed risks relating to the development, enhancement, maintenance, protection and exploitation (DEMPE) of the intangibles within the transaction. In particular, MNEs should determine which parties control any outsourced functions, and control specific, economically significant risks. As the Guidelines explain, some functions have a significant impact on the value of an intangible. If the legal owner outsources these functions to associated enterprises, then those entities should be compensated with a fair share of the returns gained from the exploitation of the intangible5.

For self-developed intangibles, or intangibles that may be used for development in the future, these functions may include:

- Design and control of research and marketing

- Direction and management of creative tasks

- Strategic decision-making for the intangible’s development

- Budget management and control

Important functions that relate to all intangibles (either self-developed or acquired) include:

- Decision-making regarding the intangible’s protection;

- Quality control over functions performed by independent or associated enterprises that may affect the intangible’s value;

The functional analysis will clarify which parties contributed to the value of the profit-generating intangibles within a transaction and help MNEs determine fair compensation.

1.4 Compare contractual terms with party conduct

MNEs need to assess whether the terms of the contractual arrangements (outlined in Step 2 above) are consistent with the conduct of the relevant parties. This involves analyzing whether associated enterprises have followed the contractual terms as per the principles outlined in the Guidelines – how the responsibilities, risks and anticipated outcomes arising from their interaction were intended to be divided at the time of entering into the contract6. This step is designed to determine whether the party that contractually assumed economically significant risks actually controls the risk and is financially able to assume the risks relating to DEMPE.

If all parties have fulfilled their contractual obligations and this conduct is consistent with the contractual arrangements, then the delineated transaction can be priced, also taking into account appropriate compensa- tion for risk management functions (step 6)7. If a party that is contractually obliged to assume risk does not control the risk or does not have financial capacity to control the risk, then the risk must be allocated to the enterprise that does8.

1.5 Delineate the actual controlled transactions

MNEs should now be able to precisely outline the actual controlled transactions related to DEMPE. As per Paragraph 6.34 of the Guidelines, this process should take into account the legal ownership of the intangibles, relevant contractual relations, and the conduct of the parties, including their relevant contributions of functions, assets and risks.

The steps in the process set out in the rest of this section for analysing risk in a controlled transaction, in order to accurately delineate the actual transaction in respect to that risk, can be summarised as follows:

- Identify economically significant risks with specificity;

- Determine how specific economically significant risks are contractually assumed by the associated enterprises under the terms of the transaction;

- Determine through a functional analysis how the associated enterprises that are parties to the transaction operate in relation to assumption and management of the specific, economically significant risks, and in particular which enterprise or enterprises perform control functions and risk mitigation functions, which enterprise or enterprises encounter upside or downside consequences of risk outcomes, and which enterprise or enterprises have the financial capacity to assume the risk;

- Steps 2-3 will have identified information relating to the assumption and management of risks in the controlled transaction. The next step is to interpret the information and determine whether the contractual assumption of risk is consistent with the conduct of the associated enterprises and other facts of the case by analysing (i) whether the associated enterprises adhere to the contractual terms; and (ii) whether the party assuming risk, as analysed under (i), exercises control over the risk and has the financial capacity to assume the risk;

- Where the party assuming risk under steps 1-4 (i) does not control the risk or does not have the financial capacity to assume the risk, apply the guidance on allocating risk; and

- The actual transaction as accurately delineated by considering the evidence of all the economically relevant characteristics of the transaction as set out in, should then be priced taking into account the financial and other consequences of risk assumption, as appropriately allocated, and appropriately compensating risk management functions.

1.6 Determine arm’s length prices for the transactions

The final step of the OECD’s framework for analyzing transactions involving intangibles is to determine, where possible, arm’s length prices for the transactions in question. Section D.2 of the Guidelines discusses situations in which transactions may be disregarded, and perhaps replaced, for transfer pricing purposes Prices should be “consistent with each party’s contributions of functions performed, assets used, and risks assumed, unless the guidance in Section D.2 of Chapter 1 applies9”. It states:

“The key question in the analysis is whether the actual transaction possesses the commercial rationality of arrangements that would be agreed between unrelated parties under comparable economic circumstances, not whether the same transaction can be observed between independent parties […] the mere fact that the transaction may not be seen between independent parties does not mean that it does not have characteristics of an arm’s length arrangement10”.

We can refer to the following illustrations as presented in the Guidelines:

Contractual Assignment of Rights

Illustration I11

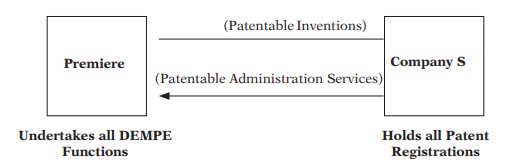

- Premiere is the parent company of an MNE group. Company S is a wholly owned subsidiary of Premiere and a member of the Premiere group. Premiere funds R&D and performs ongoing R&D functions in support of its business operations. When its R&D functions result in patentable inventions, it is the practice of the Premiere group that all rights in such inventions be assigned to Company S in order to centralise and simplify global patent administration. All patent registrations are held and maintained in the name of Company S.

- Company S employs three lawyers to perform its patent administration work and has no other employees. Company S does not conduct or control any of the R&D activities of the Premiere group. Company S has no technical R&D personnel, nor does it incur any of the Premiere group’s R&D expenses. Key decisions related to defending the patents are made by Premiere management, after taking advice from employees of Company S. Premiere’s management, and not the employees of Company S, controls all decisions regarding licensing of the group’s patents to both independent and associated enterprises. The below table provides a summary of DEMPE functions performed by each entity within the MNE.

|

DEMPE Functions |

Performed by ‘P’ |

Performed by ‘S’ |

| R&D Funding | ✓ | X |

| R&D Function | ✓ | X |

| Defending Patents | ✓ | X |

| Decisions on Licensing | ✓ | X |

| Patent Administration | X | ✓ |

- At the time of each assignment of rights from Premiere to Company S, Company S makes a nominal EUR 100 payment to Premiere in consideration of the assignment of rights to a patentable invention and, as a specific condition of the assignment, simultaneously grants to Premiere an exclusive, royalty free, patent licence, with full rights to sub-licence, for the full life of the patent to be registered. The nominal payments of Company S to Premiere are made purely to satisfy technical contract law requirements related to the assignments and, for purposes of this example, it is assumed that they do not reflect arm’s length compensation for the assigned rights to patentable inventions. Premiere uses the patented inventions in manufacturing and selling its products throughout the world and from time to time sub-licens- es patent rights to others. Company S makes no commercial use of the patents nor is it entitled to do so under the terms of the licence agreement with Premiere.

- Under the agreement, Premiere performs all functions related to the development, enhancement, maintenance, protection and exploitation of the intangibles except for patent administration services. Premiere contributes and uses all assets associated with the development and exploitation of the intangible and assumes all or substantially all of the risks associated with the intangibles. Premiere should be entitled to the bulk of the returns derived from exploitation of the intangibles. Tax administrations could arrive at an appropriate transfer pricing solution by delineating the actual transaction undertaken between Premiere and Company S. Depending on the facts, it might be determined that taken together the nominal assignment of rights to Company S and the simultaneous grant of full exploitation rights back to Premiere reflect in substance a patent administration service arrangement between Premiere and Company S. An arm’s length price would be determined for the patent administration services and Premiere would retain or be allocated the balance of the returns derived by the MNE group from the exploitation of the patents.

Illustration II

- The facts related to the development and control of patentable inventions are the same as in Example 1. However, instead of granting a perpetual and exclusive licence of its patents back to Premiere, Company S, acting under the direction and control of Premiere, grants licences of its patents to associated and independent enterprises throughout the world in exchange for periodic royalties. For purposes of this example, it is assumed that the royalties paid to Company S by associated enterprises are all arm’s length.

- Company S is the legal owner of the patents. However, its contributions to the development, enhancement, maintenance, protection, and exploitation of the patents are limited to the activities of its three employees in registering the patents and maintaining the patent registrations. The Company S employees do not control or participate in the licensing transactions involving the patents. Under these circumstances, Company S is only entitled to compensation for the functions it performs. Based on an analysis of the respective functions performed, assets used, and risks assumed by Premiere and Company S in developing, enhancing, maintaining, protecting, and exploiting the intangibles, Company S should not be entitled ultimately to retain or be attributed income from its licensing arrangements over and above the arm’s length compensation for its patent registration functions.

- As in Example 1 the true nature of the arrangement is a patent administration service contract. The appropriate transfer pricing outcome can be achieved by ensuring that the amount paid by Company S in exchange for the assignments of patent rights appropriately reflects the respective functions performed, assets used, and risks assumed by Premiere and by Company S. Under such an approach, the compensation due to Premiere for the patentable inventions is equal to the licensing revenue of Company S less an appropriate return to the functions Company S performs.

Illustration III

- The facts are the same as in Example 2. However, after licensing the patents to associated and independent enterprises for a few years, Company S, again acting under the direction and control of Premiere, sells the patents to an independent enterprise at a price reflecting appreciation in the value of the patents during the period that Company S was the legal owner. The functions of Company S throughout the period it was the legal owner of the patents were limited to performing the patent registration functions described in Examples 1 and 2.

- Under these circumstances, the income of Company S should be the same as in Example 2. It should be compensated for the registration functions it performs, but should not otherwise share in the returns derived from the exploitation of the intangibles, including the returns generated from the disposition of the intangibles.

In each one of the three illustrations above, we find that contractually, ‘S’ was assigned the Patent Rights and was the legal owner of the intangibles. However, in terms of DEMPE functions, it was ‘P’ that undertook the deci- sion-making and assumed the associated risks. Therefore, in line with the

OECD approach, conduct was accorded precedence over the contract and return on intangible must flow to ‘P’. ‘S’ is only entitled to a routine return for patent administration services.

2. Lessons for MNEs

2.1 Reassess Capabilities

MNEs need to examine their value chain proactively to identify possible mismatches between location of economic activity, and the resultant value creation, to avoid any disputes at a later date. They also need to review the actual conduct of different group entities, rather than focusing merely on documentation or paper trails in the form of inter-company agreements to justify their intra-group transactions. Although “substance over form” has always been the guiding principle for any transfer pricing analysis in India, the new BEPS regime has pushed it to the centre stage.

For instance, parking of intangibles in low-tax or no-tax jurisdictions, with no economic substance in such entities, could be a potential BEPS risk area. Revised guidance requires that a FAR analysis or capacity reassessment be carried out for such entities. This will help in evaluating whether they have the capability to perform intangible related functions (such as development, exploitation, etc.,) and bear the associated risks (such as financial risk, obsolescence risk, failure risk, infringement risk, etc.,) or are mere shell entities to avail tax benefits.

Another typical situation wherein similar risk may arise can be an intra-group services scenario, which is quite common in Indian context. The taxpayers would need to substantiate the capability of service providers to render services in terms of availability of necessary resources like fixed assets, employees with relevant skill sets, etc.

2.2 Reassess Agreements

In the long run, MNEs need to be more careful and cautious in their approach to any structuring/re-structuring exercise and take necessary corrective steps, wherever required. Intra-group agreements often serve as the starting point for a transfer pricing analysis. They help in gathering basic understanding of how a transaction is structured. Although the revisited guidelines focus on facts of the actual transaction, inclusion of any clause in an intra-group agreement that is not in alignment with the actual conduct may result in unnecessary dispute and litigation. A more pragmatic solution, therefore, would be to restructure the transaction to cover any BEPS-related risks and thereafter align the intra-group agreement with the actual transaction.

- Para 6.6 of TPG, 2022.

- Paras 1.71 and 1.72 of OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines, 2022.

2a. Para 1.42 of TPG, 2022. - Para 6.34 of TPG, 2022.

- Para 6.42 of TPG, 2022.

- 5. Para 6.56 of TPG, 2022.

- Para 1.42 of TPG, 2022.

- Para 1.60 of TPG, 2022.

- Para 1.98 of TPG, 2022.

- Para 6.34 of TPG, 2022.

- Para 1.123 of TPG, 2022.

- Para 1.148 of TPG, 2022.

Disclaimer: The content/information published on the website is only for general information of the user and shall not be construed as legal advice. While the Taxmann has exercised reasonable efforts to ensure the veracity of information/content published, Taxmann shall be under no liability in any manner whatsoever for incorrect information, if any.

Taxmann Publications has a dedicated in-house Research & Editorial Team. This team consists of a team of Chartered Accountants, Company Secretaries, and Lawyers. This team works under the guidance and supervision of editor-in-chief Mr Rakesh Bhargava.

The Research and Editorial Team is responsible for developing reliable and accurate content for the readers. The team follows the six-sigma approach to achieve the benchmark of zero error in its publications and research platforms. The team ensures that the following publication guidelines are thoroughly followed while developing the content:

- The statutory material is obtained only from the authorized and reliable sources

- All the latest developments in the judicial and legislative fields are covered

- Prepare the analytical write-ups on current, controversial, and important issues to help the readers to understand the concept and its implications

- Every content published by Taxmann is complete, accurate and lucid

- All evidence-based statements are supported with proper reference to Section, Circular No., Notification No. or citations

- The golden rules of grammar, style and consistency are thoroughly followed

- Font and size that’s easy to read and remain consistent across all imprint and digital publications are applied

CA | CS | CMA

CA | CS | CMA