Purchasing Power Parity – Case Study

- Blog|FEMA & Banking|

- 15 Min Read

- By Taxmann

- |

- Last Updated on 22 September, 2023

The present International Monetary System is characterized by a mix of freely floating, managed floating and fixed exchange rates. As such, no single theory is available to forecast exchange rates under all conditions. This chapter provides a systematic discussion of the key international parity relationships which help to explain exchange rate movements. A thorough understanding of parity relationships is essential for efficient financial management and helps the financial manager in understanding:

-

- How to determine foreign exchange rates; and

- The process by which foreign exchange rates can be forecasted.

The two theories discussed in this chapter are the Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) theory and the International Fisher Effect (IFE). If the PPP and IFE theories hold consistently, decision making by MNCs would be much easier. Because these theories do not hold consistently, an MNC’s decision making becomes very challenging.

Table of Contents

Taxmann's International Financial Management provides an effective and detailed presentation of important concepts, and practical application in today’s global business environment, including Foreign Exchange Market, International Financial System, Eurocurrency Market

1. Introduction

The phenomenon of exchange rates movement is an important issue in international finance and managers of multinational firms, international investors, importers and exporters and government officials attach enormous importance to it. In fact, they have to deal with the issue of exchange rates every day. Yet, the determination of exchange rates remains something of a mystery. Forecasters with the most impressive records frequently go wrong in their calculations by substantial margins. However, many times poor forecasting is due to unforeseeable events. For example, at the beginning of 1984, all forecasters uniformly predicted that the dollar would decline against other major currencies. But the dollar proceeded to rise throughout the year although in other respects the general performance of the world economy did not radically depart from forecasts. This clearly shows that the theoretical models or other models used by forecasters were not correct and also that the mechanics of exchange rate determination needs to studied thoroughly.

The tremendous increase in international mobility of capital as a result of marked improvements in telecommunications all over and also lesser restrictions on international financial transactions has made the concept of exchange rate determination more complicated and difficult to understand. The above factors have often resulted in the forex market behaving like a volatile stock market. In fact, economists now have been forced to reverse their thinking about exchange rate determination.

Thus, while much remains to be learned about exchange rates, a lot is also understood about them. Exchange rates forecasts have often been wrong, though many times they have also met with impressive success. Also, when exchange rate determination has been matched against historical records, it has had much explanatory power.

Are changes in exchange rates predictable? How does inflation affect exchange rates? How are interest rate related to exchange rates? What is the ‘proper exchange rate’ in theory? For an answer to these fundamental issues, it is essential to understand the different theories of exchange rate determination.

The three theories of exchange rate determination are:

-

- Purchasing Power Parity (PPP), which links spot exchange rates to nations’ price levels.

- The Interest Rate Parity (IRP), which links spot exchange rates, forward exchange rates and nominal interest rates. (Already discussed in chapter 8)

- The International Fisher Effect(IFE), which links exchange rates to nations’ nominal interest rate levels.

2. Purchasing Power Parity (PPP)

The PPP theory focuses on the inflation-exchange rate relationships. If the law of one price were true for all goods and services, we could obtain the theory of PPP. There are two forms of the PPP theory.

2.1 Absolute Purchasing Power Parity

The absolute PPP theory postulates that the equilibrium exchange rate between currencies of two countries is equal to the ratio of the price levels in the two nations. Thus, prices of similar products of two different countries should be equal when measured in a common currency as per the absolute version of PPP theory.

A Swedish economist, Gustav Cassel, popularised the PPP in the 1920s. When many countries like Germany, Hungary and Soviet Union experienced hyperinflation in those years, the purchasing power of the currencies in these countries sharply declined. The same currencies also depreciated sharply against the stable currencies like the US dollar. The PPP theory became popular against this historical backdrop.

Let Pa refer to the general price level in nation A, Pb the general price level in nation B and Rab to the exchange rate between the currency of nation A and currency of nation B. Then the absolute purchasing power parity theory postulates that

Rab = Pa/Pb

For example, if nation A is the US and nation B is the UK, the exchange rate between the dollar and the pound is equal to the ratio of US to UK Prices. For example, if the general price level in the US is twice the general price level in the UK, the absolute PPP theory postulates the equilibrium exchange rate to be Rab = $2/£1.

In reality, the exchange rate between the dollar and the pound could vary considerably from $2/£1 due to various factors like transportation costs, tariffs, or other trade barriers between the two countries. This version of the absolute PPP has a number of defects. First, the existence of transportation costs, tariffs, quotas or other obstructions to the free flow of international trade may prevent the absolute form of PPP. The absolute form of PPP appears to calculate the exchange rate that equilibrates trade in goods and services so that a nation experiencing capital outflows would have a deficit in its BOP while a nation receiving capital inflows would have a surplus. Finally, the theory does not even equilibrate trade in goods and services because of the existence of non-traded goods and services.

Non-traded goods such as cement and bricks, for which the transportation cost is too high, cannot enter international trade except perhaps in the border areas. Also, specialised services like those of doctors, hairstylists, etc., do not enter international trade. International trade tends to equate the prices of traded goods and services among nations but not the prices of non-traded goods and services. The general price level in each nation includes both traded and non-traded goods and since the prices of non-traded goods are not equalised by international trade, the absolute PPP will not lead to the exchange rate that equilibrates trade and has to be rejected.

2.2 Relative Purchasing Power Parity

The relative form of PPP theory is an alternative version which postulates that the change in the exchange rate over a period of time should be proportional to the relative change in the price levels in the two nations over the same time period. This form of PPP theory accounts for market imperfections such as transportation costs, tariffs and quotas. Relative PPP theory accepts that because of market imperfections prices of similar products in different countries will not necessarily be the same when measured in a common currency. What it specifically states is that the rate of change in the prices of products will be somewhat similar when measured in a common currency as long as the trade barriers and transportation costs remain unchanged.

Specifically, if subscript ‘0’ refers to the base period and ‘1’ to a subsequent period then relative PPP theory postulates that

![]()

where Rab1 and Rab0 refer to the exchange rates in period 1 and in the base period respectively.

If the absolute PPP were to hold true, the relative PPP would also hold. However, the vice versa need not hold. For example, obstructions to the free flow of international trade like transportation costs, existence of capital flows, government intervention policies, etc. would lead to the rejection of the absolute PPP. However, only a change in these factors would lead to the rejection of the relative PPP.

Other problems with the relative PPP theory are: first, ratio of prices of non-traded goods to the prices of traded goods and services is consistently higher in developed nations than in developing nations, e.g., the services of beauticians, hairstylists, etc., are more costly in developed nations than in developing nations. This is partly due to the fact that in developed nations, for labour to remain in these occupations, it must receive wages somewhat comparable to the high wages in the production of traded goods and services. The result is that prices of non-traded goods and services is much higher in developed than in developing countries. Second, the general price level index includes the prices of both traded and non-traded goods and services and the prices of non-traded goods are not equalised by international trade but are relatively higher in developed nations. The result of the above is that the relative PPP theory will tend to undervalue exchange rates for developed nations and overvalue exchange rates for developing nations with distortions being greater the greater the differences in the levels of development. Finally, since various factors other than relative price levels can influence exchange rates in the short run, it can hardly be expected that the relative PPP will result in an accurate forecast.

In spite of the above deficiencies, empirical tests have indicated that the relative PPP theory often gives fairly good approximations of the equilibrium exchange rate, particularly in periods of high inflation. Second, the PPP holds well over the very long run but poorly for shorter time periods.

2.3 Graphic Analysis of PPP

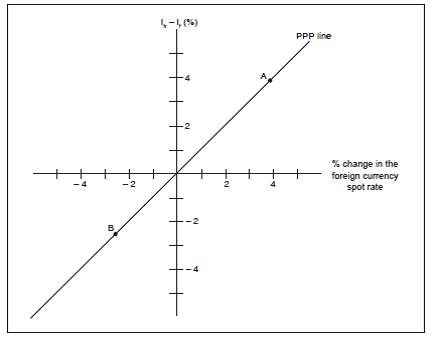

Exhibit 9.1 shows the Purchasing Power Parity theory which helps us to assess the potential impact of inflation on exchange rates. The vertical axis measures the percentage appreciation or depreciation of the foreign currency relative to the home currency while the horizontal axis measures the percentage by which the inflation in the foreign country is higher or lower relative to the home country. The points in the diagram show that given the inflation differential between the home and the foreign country, say by X per cent, the foreign currency should adjust by X per cent due to the differential in inflation rates. The diagonal line connecting all these points together is known as the PPP line and it depicts the equilibrium position between a change in the exchange rates and relative inflation rates.

Purchasing Power Purity Theory

For example, point A represents an equilibrium point where inflation in the foreign country, say UK, is 4% lower than the home country, say India, so that Ih – If = 4%. This will lead to an appreciation of the British pound by 4% per annum with respect to the Indian rupee.

Point B in the diagram shows a point where the difference in the inflation rates in India and Mexico is assumed to be 3% so that Ih – If = – 3%. This will lead to an anticipated depreciation of the Mexican peso by 3 per cent, as depicted by point B. If the exchange rate responds to inflation differentials according to the PPP, the points will lie on or close to the PPP line.

2.4 Empirical Testing of PPP Theory

Substantial empirical research has been done to test the validity of PPP theory. The general conclusions of most of these tests have been that PPP does not accurately predict future exchange rates and that there are significant deviations from PPP persisting for lengthy periods.

3. International Fisher Effect (IFE)

The IFE uses interest rates rather than inflation rate differential to explain the changes in exchange rates over time. IFE is closely related to the PPP because interest rates are significantly correlated with inflation rates. The relationship between the percentage change in the spot exchange rate over time and the differential between comparable interest rates in different national capital markets is known as the ‘International Fisher Effect.’

The IFE suggests that given two countries, the currency in the country with the higher interest rate will depreciate by the amount of the interest rate differential. That is, within a country, the nominal interest rate tends to approximately equal the real interest rate plus the expected inflation rate. Both, theoretical considerations and empirical research, had convinced Irving Fisher that changes in price level expectations cause a compensatory adjustment in the nominal interest rate and that the rapidity of the adjustment depends on the completeness of the information possessed by the participants in financial markets. The proportion that the nominal interest rate varies directly with the expected inflation rate, known as the ‘Fisher effect’, has subsequently been incorporated into the theory of exchange rate determination. Applied internationally, the IFE suggests that nominal interest rates are unbiased indicators of future exchange rates.

A country’s nominal interest rate is usually defined as the risk free interest rate paid on a virtually costless loan. Risk free in this context refers to risks other than inflation.

In an expectational sense, a country’s real interest rate is its nominal interest rate adjusted for the expected annual inflation rate. It can be viewed as the real amount by which a lender expects the value of the funds lent to increase on an annual basis. For a firm using its own funds, it can be viewed as the expected real cost of doing so. The nominal interest rate consists of a real rate of return and anticipated inflation. The nominal interest rate would also incorporate the default risk of an investment.

It is often argued that an increase in a country’s interest rates tends to increase the exchange value of its currency by inducing capital inflows. However, the IFE argues that a rise in a country’s nominal interest rate relative to the nominal interest rates of other countries indicates that the exchange value of the country’s currency is expected to fall. This is due to the increase in the country’s expected inflation and not due to the increase in the nominal interest rate. The IFE implies that if the nominal interest rate does not sufficiently increase to maintain the real interest rate, the exchange value of the country’s currency tends to decline even further.

3.1 Graphic Analysis of the International Fisher

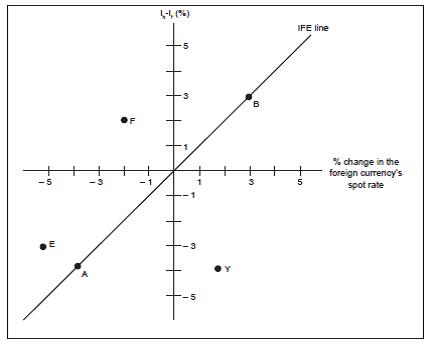

The exibit given below illustrates the IFE. The X axis shows the percentage change in the foreign currency’s spot rate while the Y axis shows the difference between the home interest rate and the foreign interest rate (Ih-If). The diagonal line indicates the IFE line and depicts the exchange rate adjustment to offset the differential in interest rates. For all points on the IFE line, an investor will end up achieving the same yield (adjusted for exchange rate fluctuations) whether investing at home or in a foreign country.

Illustration of IFE Line (When exchange rate changes perfectly offset interest rate differentials)

Point A in the diagram shows a situation where the foreign interest exceeds the home interest rate by 4 percentage points, yet, the foreign currency depreciates by 4 per cent to offset its interest rate advantage. This would mean that an investor setting up a deposit in the foreign country would have achieved a return similar to what was possible domestically. Point B represents a home interest rate 3 per cent above the foreign interest rate. If investors from the home country establish a foreign deposit, they will be at a disadvantage regarding the foreign interest rate. But the IFE theory suggests that the currency should appreciate by 3 per cent to offset the interest rate disadvantage.

Also, the IFE suggests that if a company regularly makes foreign investments to take advantage of higher foreign interest rates, it will achieve a yield that is sometimes below and sometimes above the domestic yield.

Points above the IFE line like E and F reflect lower returns from foreign deposits than the returns that are possible domestically. For example, point E represents a foreign interest rate that is 3 per cent above the home interest rate. Yet, point E suggests that the exchange rate of the foreign currency depreciated by 5 per cent to more than offset its interest rate disadvantage.

Points below the IFE line show that the firm earns higher returns from investing in foreign deposits. For example, consider point Y in the diagram. The foreign interest rate exceeds the home interest rate by 4 per cent. The foreign currency also appreciated by 2 per cent. The combination of the higher foreign interest rate plus the appreciation of the foreign currency will cause the foreign yield to be higher than what was possible domestically. If an investor were to compile and plot the actual data and if a majority of the points were to fall below the IFE, this would suggest that the investors of the home country could have consistently increased their investment returns by investing in foreign bank deposits. Such results refute the IFE theory.

4. Comparison of PPP, IFE and IRP Theories

The table given below compares three related theories of international finance, namely (i) Interest Rate Parity (IRP) (ii) Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) and (iii) the International Fisher Effect (IFE). All three theories relate to the determination of exchange rates. Yet, they differ in their implications. The theory of IRP focuses on why the forward rate differs from the spot rate and the degree of difference that should exist. This relates to a specific point in time. The, PPP theory and IFE theory focus on how a currency’s spot rate will change over time. While PPP theory suggests that the spot rate will change in accordance with inflation differentials, IFE theory suggests that it will change in accordance with interest rate differential.

Comparison of HRP, PPP and IFE Theories

|

Theory |

Key Variables of Theory |

Summary of Theory |

|

| Interest rate party (IRP) | Forward rate premium (or discount) | Interest differential | The forward rate of one currency with res-pect to another will contain a premium (or discount) that is determined by the differential in interest rates between the two countries. As a result, covered interest arbitrage will provide a return that is no higher than a domestic return. |

| Purchasing Power (Parity (PPP)) | Percentage change in spot exchange rate | Inflation rate differential | The spot rate of one currency with respect to another will change in reaction to the differential in inflation rates between the two countries. Consequently, the purchasing power for consumers when purchasing goods in their own country will be similar to their purchasing power when importing goods from the foreign country. |

| International Fisher Effect (IFE) | Percentage change in spot exchange rate | Interest rate differential | The spot rate of one currency with respect to another will change in accordance with the differential in interest rates between the two countries. Consequently, the return on uncovered foreign money market securities will, on an average, be no higher than the return on domestic money market securities from the perspective of investors in the home country. |

Source: Jeff Madura, ‘International Financial Management”

5. Summary

At the cornerstone of international finance relations, are the three international interest parity conditions, viz., the covered interest parity, the PPP doctrine and the international fisher effect. These parity conditions indicate degree of market integration of the domestic economy with the rest of the world.

The PPP theory focuses on the inflation-exchange rate relationship. Substantial empirical research has been done to test the validity of PPP theory. The general consensus has been that PPP does not accurately predict future exchange rates and there are significant deviations from PPP persisting for lengthy periods.

The IFE uses interest rates rather than inflation rate differential to explain the changes in exchange rates over time. IFE is closely related to PPP because interest rates are significantly correlated with inflation rates.

6. Solved Problems

Q1. Explain the rationale behind Purchasing Power Parity.

Ans. When inflation is high in a particular country foreign demand for goods in that country will decrease. In addition, that country’s demand for foreign goods should increase. Thus, the home currency of that country will weaken; this tendency should continue until the currency has weakened to the extent that a foreign country’s goods are no more attractive than the home country’s goods. Inflation differentials are offset by exchange rate changes.

Q2. Explain how you could determine whether Purchasing Power Parity exists.

Ans. One method is to choose two countries and compare the inflation differential to the exchange rate change for several different periods. Then determine whether the exchange rate changes were similar to what would have been expected under PPP theory.

A second method is to choose a variety of countries and compare the inflation differential of each foreign country relative to the home country for a given period. Then, determine whether the exchange rate changes of each foreign currency were what would have been expected based on the inflation differentials under PPP theory.

Q3. Explain why Purchasing Power Parity does not hold.

Ans. PPP does not consistently hold because there are other factors besides inflation that influence exchange rates. Thus, exchange rates will not move in perfect tandem with inflation differentials. In addition, there may not be substitutes for traded goods. Therefore, even when a country’s inflation increases, the foreign demand for its products may not necessarily decrease (in the manner suggested by PPP) if substitutes are not available.

Q4. How is it possible for Purchasing Power Parity to hold if the International Fisher Effect does not?

Ans. For the IFE to hold, the following conditions are necessary:

(a) Investors across countries require the same real returns.

(b) The expected inflation rate embedded in the nominal interest rate occurs.

(c) The exchange rate adjusts to the inflation rate differential according to PPP

If conditions (i) or (ii) do not hold, PPP may still hold, but investors may achieve consistently higher returns when investing in a foreign country’s securities. Thus, IFE would be refuted.

Q5. Explain why the International Fisher Effect may not hold.

Ans. Exchange rate movements react to other factors in addition to interest rate differentials. Therefore, an exchange rate will not necessarily adjust in accordance with the nominal interest rate differentials, so that IFE may not hold.

7. Case Study

7.1 Parity Conditions in International Finance

At the cornerstone of international finance relations, lie the PPP doctrine and the three international interest parity conditions, viz. the Covered Interest Parity (CIP), the Uncovered Interest parity (UIP) and the Fisher’s Real Interest Parity (RIP). These parity conditions indicate the degree of market integration of the domestic economy with the rest of the world.

7.2 Indian Evidence

Empirical estimates of parity conditions are plagued with theoretical and econometric difficulties that make conclusions difficult even in the case of well developed markets. Differences in estimates arise primarily from model specifications, choice techniques and due to sample periods over which the models are estimated. Theoretical difficulties arise from the existence of trade restrictions, transport and transaction costs, as also from rate consumption and interest rate smoothing behaviour. In practice, persistent swings in real exchange rate are observed. For India, Pattanaik (1999) finds that PPP over the long run defines the presence of a co-integrated relationship between exchange rate and relative prices and the misalignment at any point of time is corrected by 7.7 per cent per quarter through nominal exchange rate adjustments. Bhoi and Dhal (1998) tested for the relevance of UIP and CIP and concluded that neither holds true.

7.3 Other Countries

Much research has been conducted to test whether PPP exists. Various studies in US have found evidence of significant deviations from PPP, persistently for lengthy periods.

Whether the IFE holds true in reality depends on the particular time period examined. In 1978-79, the US interest rates were generally higher than foreign interest rates and the foreign currency values strengthened during this period, supporting IFE theory to an extent. However, during the 1980-84 period, the foreign currencies consistently weakened far beyond what would have been anticipated according to IFE theory. Also, during the 1985-87 period, foreign currencies strengthened to a much greater degree than suggested by the interest differential. Thus, IFE may hold for sometime, but there is evidence that it does not consistently hold true.

Disclaimer: The content/information published on the website is only for general information of the user and shall not be construed as legal advice. While the Taxmann has exercised reasonable efforts to ensure the veracity of information/content published, Taxmann shall be under no liability in any manner whatsoever for incorrect information, if any.

Taxmann Publications has a dedicated in-house Research & Editorial Team. This team consists of a team of Chartered Accountants, Company Secretaries, and Lawyers. This team works under the guidance and supervision of editor-in-chief Mr Rakesh Bhargava.

The Research and Editorial Team is responsible for developing reliable and accurate content for the readers. The team follows the six-sigma approach to achieve the benchmark of zero error in its publications and research platforms. The team ensures that the following publication guidelines are thoroughly followed while developing the content:

- The statutory material is obtained only from the authorized and reliable sources

- All the latest developments in the judicial and legislative fields are covered

- Prepare the analytical write-ups on current, controversial, and important issues to help the readers to understand the concept and its implications

- Every content published by Taxmann is complete, accurate and lucid

- All evidence-based statements are supported with proper reference to Section, Circular No., Notification No. or citations

- The golden rules of grammar, style and consistency are thoroughly followed

- Font and size that’s easy to read and remain consistent across all imprint and digital publications are applied

CA | CS | CMA

CA | CS | CMA