Impact of GST on Immovable Property Transactions

- Blog|GST & Customs|

- 17 Min Read

- By Taxmann

- |

- Last Updated on 4 July, 2024

The impact of GST on immovable property transactions is multifaceted. Firstly, under the aspect theory of taxation, GST can apply to immovable property transactions by distinguishing between different taxable events such as manufacture and sale. Certain articles like securities, money, and specified petro-products are expressly excluded from GST. It is important to note that paying stamp duty on immovable property transactions does not exempt these transactions from GST; stamp duty is paid on the instrument of conveyance, while GST is payable on the transaction consideration. The definition of 'service' under GST is broad, meaning almost all transactions are subject to GST unless explicitly excluded, reflecting the purpose of the 101st Constitutional Amendment. Legal guidance from courts emphasizes the importance of using statutory definitions and precedents to accurately determine GST liability. Additionally, the manner and purpose of affixation of objects to land or buildings are critical in determining whether they are considered immovable property and thus subject to GST. Rights related to immovable property, such as leases or development rights, are also considered immovable property and can attract GST. Moreover, rights to future benefits from land, such as harvesting crops or mining minerals, are treated as immovable property and are subject to GST. Understanding these aspects helps ensure compliance and accurate tax treatment for immovable property transactions under GST.

Table of Contents

Check out Taxmann's GST & Allied Laws which provides a comprehensive commentary into the realm of GST and its correlation with the foundational laws in India, such as the Indian Contract Act 1872, the Transfer of Property Act 1882, and the Limitation Act 1963, among others. Aimed at legal practitioners, policymakers, and businesses, it explains foundational principles and legislative intricacies governing GST, enhancing readers' ability to navigate legal and procedural challenges.

1. Relevance of GST

Erroneous to think that GST cannot apply to transactions involving immovable property. In Province of Madras v. Boddu Paidanna & Sons AIR 1942 FC 33 (affirmed in appeal in Governor-General v. Province of Madras AIR 1945 PC 98 and quoted with approval in Atiabari Tea Co. v. State of Assam AIR 1961 SC 232) when demand for Central Excise duty was made on manufacture of pressed cake after extraction of groundnut oil (oil-cake) that were sold on payment of applicable sales tax, taxpayer resisted the demand citing ‘double taxation’. Apex Court held that Central Excise duty applies for the taxable event of manufacture whereas Sales tax applies in respect of the taxable event of sale (of those manufactured articles). And although selling price may form basis for quantification of both, there is no double taxation. This might be the simplest presentation of ‘aspect theory’ of taxation.

Exclusion from incidence of GST demands that:

- levy must be expressly made inapplicable to articles such as securities, money, alcoholic liquor and 5 petro-products;

- transactions kept out of the incidence of tax in Schedule III;

- statutory exemption notified under section

Payment of stamp duty in respect of transactions involving immovable property does not procure immunity from the incidence of GST without showing that these transactions fall within one of the three situations listed above for definitive exclusion from the incidence. Stamp duty is paid on the instrument of conveyance and GST is payable on the consideration for the transaction.

When “service means anything…….”, it is important to appreciate that ‘anything includes everything and leave nothing” unless expressly left out. To assume that GST ought not to apply without showing which of these three situations cover a transaction would be an impoverished grasp of the purpose for which 101st Amendment was made. And when article 246A opens with a non obstante clause, aides to article 246A such as Schedule VII and the three lists in it, cannot pollinate deliberations in GST.

In order not to falter with immovable property and to locate the contours of the limited exclusion allowed in Schedule III of Central GST Act qua immovable property transactions, it is most essential to engage in deep study of this subject. And Mulla’s work in this area are inescapable for a thorough understanding. Some relevant aspects are presented in this deliberation.

2. Immovable Property

2.1 Statutory Definitions

Expressions that have a statutory definition cannot be substituted with expectations about those expressions. And neither exclusion from the definition cannot be forcibly included to suit the needs of a certain tax treatment nor inclusions in the definition shunted out.

Great struggle is evident in the manner in which ‘immovable property’ has been defined and Apex Court had to intervene to declare that the definition in these legislations must be referred for purposes of gaining a well-rounded understanding for purposes of this Act:

| Transfer of Property Act | Registration Act | General Clauses Act |

| Section 3 “Immovable Property” does not include standing timber, growing crops or grass; | Section 2(6) “Immovable Property” includes land, buildings, hereditary allowances, rights to ways, lights, ferries, fisheries or any other benefit to arise out of land, and things attached to the earth, or permanently fastened to anything which is attached to the earth, but not standing timber, growing crops nor grass; | Section 3(26) “Immovable Property” shall include land, benefits to arise out of land, and things attached to the earth, or permanently fastened to anything attached to the earth; |

*Article 367 of Constitution states that General Clauses Act, 1897 is applicable even to interpret the Constitution.

This struggle is not without good reason so as not to include those to be excluded and exclude those to be included. Illustrations in the definitions are instructive. Apex Court held in Tarakeshwar Sia Thakurji v. Dar Das Dey Co. (1979) 3 SCC 106 that definition in section 3(26) of General Clauses Act applies to Transfer of Property Act since the definition in section 3 is in the negative, drawing authority from Shantabai v. State of Bombay AIR 1958 SC 532 and before that in Mohammed Ibrahim v. Northern Circars Fibre Trading AIR 1944 Mad 492.

2.2 Affixation

‘Able’ in immovable, refers to character of the thing and not capability of any person, to move it. Character goes to ‘manner and purpose’. Capability (of a person or process) does to ‘strength and ability’. Manner of affixation is to render the thing fastened so that it is inextricably bonded with the land or building, to which it is affixed. Method used guides the conviction about the inextricable bond that is sought to be established.

Example (309): Hut is immovable property.

Example (310): Gypsum partition walls with aluminium or wooden frame is immovable property.

Example (311): Ducts for air-handling (low-side) is movable property.

Example (312): ATM installed in movable property.

Purpose of affixation must also show a sub-optimal functionality if the thing were not affixed. Functionality is not general functionality but that suited for the person’s needs. Method used also guides this relation to show that it is commensurate with the objective of rendering the thing immovable.

Example (313): Diesel based power generating (DG) installation is movable property although bolted to concrete floor.

Example (314): Container houses used for dwelling or as office is movable property.

To be unearthed, with or without damage, is no reason to doubt the results of the ‘manner and purpose’ tests administered. To say that the thing affixed can be easily dismantled does not undermine the objective of its affixation. There is nothing in the ‘manner and purpose’ test that requires impairment (on dismantling) an necessary to admit permanence in its affixation.

Tier 2 affixation where an article is ‘attached to that which is embedded’ to earth is also immovable property provided it satisfies the ‘method and purpose’ test.

“It is nobody’s case that the attachment of the plant to the foundation is meant for permanent beneficial enjoyment of either the foundation or the land in which the same is embedded”

– CCE v. Solid and Correct Engineering Works 2010 (252) ELT 481 (SC)

Building is also a poorly appreciated expression. Factory building may be constructed, and machinery installed inside the building. Alternatively, machinery may be installed, and then protective enclosure may be added in cover the machinery. And it matters if the enclosure-building is part of the machinery or independent of the machinery. And the ‘manner and purpose’ test reveals that the enclosure-building may be:

- Means of operating the machinery;

- Premises where machinery is operated.

Example (315): Acoustic enclosure is part of DG set and not a building.

Example (316): Projector room in cinema theatre is building.

2.3 Standing timber

Tree is the most telling example of ‘immovable’ and application of ‘manner and purpose’ test reveals the dependence on land is inalienable for the sapling to derive nourishing and grow to become a tree. But standing timber to be excluded in the definition in section 3 indicates the importance of the choice of words – tree v. standing timber. Standing timber is a tree that is ready for felling. Tree that has reached the end of its dependence on land for nourishment and sustenance and left to itself may continue (or die) but is unlikely to derive any more from that land having already reached the goal of its planting. This is an important understanding to locate the legal purpose of defining ‘immovable property’ to guide treatment when it is the object of contract in different transactions. By the ‘manner and purpose’ test, tree would be immovable property since it is not intended for felling, but when this tree reaches the desired or optimal extent of growth and becomes standing timber, it would NOT remain immovable property if taken up for filling. Of course, there should not be any doubt that tree excludes plant and scientific tests provide the distinction.

Example (317): Tomato plant bearing fruit (tomato) is a tree.

Example (318): Teakwood plant more than 6 cms. girth is a tree.

Example (319): Sprouted seeds is a plant and not a tree.

Example (320): Coconut sapling is a plant and not a tree.

Common parlance cannot be of much assistance and only after some (or substantial) refinement will the meaning begin to unfold, and implications become understandable.

2.4 Growing crop

Standing timber are on the other side of their life which growing crop have not yet reached. And for this reason, growing crop are excluded from immovable property. When land is sold with growing crop on it, they both form a whole and inseparable ‘object’ of this contract, and for this reason the combined object of transfer will be immovable property. But where the land is leased to an occupier for 10 years, the terms of lease is not for occupier to enjoy the land (with growing crop on it), but to harvest the growing crop once they become full grown and ready for harvest.

Example (321): Lease of land with fruit-bearing trees for 6 months is nothing but price paid for the fruit ready for harvest. Note the restriction against felling those trees.

Example (322): Lease of land for 5 years is not price paid for sale of fruit because this lease gets rights to harvest over multiple seasons. Note any restrictions against felling those trees, especially, if that variety have more than 10 fruit-bearing years and much of it still remain.

After all, duration of lease for 10 years is to allow for growing crop to grow and be harvested. And this land is be returned at the end of the term with- out any stipulation that the crop must also be returned ‘as it was’ unlike a stipulation when a building taken on lease requires that the building be returned in original condition, subject to normal wear and tear. Stipulation is that the land (only) must be returned along with any new additions and accretions (from last round of sowing that is not ready to harvest). Object of contract (discussed earlier) must be discerned from terms of contract and not from titles to documents.

“The principle of these decisions appears to be this, that wherever at the time of the contract it is contemplated that the purchaser should derive a benefit from the further growth of the thing sold from further vegetation and from the nutriment to be afforded by the land, the contract is to be considered as for an interest in land; but where the process of vegetation is over, or the parties agree that the thing sold shall be immediately withdrawn from the land, is to be considered a mere warehousing of the thing sold, and the contract is for goods.”

Marshall v. Green (1875) 1 CPD 35

2.5 Intangible immovable property

There is no compulsion that immovable property must be ‘tangible’. Land and building are tangible. Things attached to land and building are also tangible. Any transaction involving sale of such land, building, things attached to either of them, would be transfer (discussed later) of immovable property.

But rights qua such tangible immovable property are also immovable but intangible property. Immovable property is commonly referred to being tangible and nothing is farther from the truth that to think that intangible immovable property is impossible.

Example (323): Right to use is an intangible right over land which can be detached from ownership and be transferred under a ‘lease’.

Example (324): Fishing rights in an intangible right over the land which can be transferred under a lease of lake. Lake refers to water covering the land underneath the lake.

Example (325): Right to construct (and develop) over land is itself an intangible immovable property.

‘Property’ is not the land or building (or even goods, being movable property). Property is the right qua those things – land or building or goods. And if the thing over which ‘rights’ exist is immovable then it is immovable property and if the thing is movable then it is movable property. Property is commonly (erroneously) referred as the very thing itself and nothing is farther still from the truth.

2.6 Benefits to arise from land

Observe that the reference in this expression is to ‘future benefits’, that is, benefits ‘to’ arise which is akin to benefits ‘yet to’ arise and not benefits that ‘already’ arose. Since benefits referred are those that lie in the future then the what lies in the present is the ‘rights to those benefits’. That is, there is one kind of intangible right in present that is enforceable and allows holder of those rights to enjoy benefits when those things come into existence. There is another kind of tangible or intangible right being future benefits that are not yet enforceable until those things exist. And this ‘right in present’ can be already be transferred as per law so that the Transferee will enjoy those benefits (when they arise) leaving Transferor at present to enjoy proceeds from transfer of that right.

Transferor’s rights are intangible immovable property. Transferee’s rights are tangible property (if benefits are goods like fruits to be harvested or fish to be caught) or intangible property (if benefits are right to use (lease) or right to construct and develop). And benefits to arise from land refers to the right and not the benefit and such right is intangible immovable property.

Example (326): Fruits on a tree are benefits from land. Right to permit harvesting is benefits to arise from land.

Example (327): Ore in land are benefits from land. Right to permit mining is benefits to arrive from land.

Uncertainty of yield but certainty of ‘exclusive rights to exploit’ resources from land, is transfer of rights to future goods being benefits to arise from land. This is intangible immovable property rights. But where there is certainty of yield, it is sale of goods. Much has been deliberated about future goods and contract involving future goods being a mere promise at present to contract in future when those goods come into existence, in the context of Sale of Goods Act. And that principle contained in sections 4(3) and 6(3) of that Act is traceable to section 5 of Transfer of Property Act (discussed later) where transfer must be of property in existence and not property that is yet to come into existence. Therefore, benefits ‘to’ arise from land is only the ‘right in present’ to ‘enjoy in future’ the benefits that are attached to immovable property.

Example (328): Fruits from the next three harvests can be transferred today by entering into a non-cancellable lease of land duly registered for a term of three years.

Example (329): Irrevocable power of attorney along with interest in land can be executed.

There is some element of speculation as to the quantum of benefits (fruits or fish) that may be available but this does not impair Transferor’s authority to enter into this transaction because the ‘right in present’ is the object of transfer and not the ‘benefits in future’. As such, there is no doubt or speculation about the existence of this right in present. Lease being only the ‘form’ in which the transfer in present is made effective and enforceable. It is not without good reason that VR Krishna Iyer J observed that royalty for forest lease is a feudalistic euphemism for price of timber permitted to be extracted (although this decision was overruled in State of Orissa v. Titaghur Paper Mills Company Ltd. 1985 AIR 1293 (SC).

“We are satisfied that despite its description, the deed confers in truth and substance a right to cut and carry timber of specified species. Till the trees are cut, they remain the property of the owner, namely the appellant. Once the trees are severed, the property passes. The ‘Royalty’ is a feudalistic euphemism for the ‘price’ of the timber. We may also observe that the question before us is not so much as to what nomenclature would aptly describe the deed but as to whether the deed results in sale of trees after they are cut. The answer to that question, as would appear from the above, has to be in the affirmative.”

– State of MP. v. Orient Paper Mills Ltd. AIR 1977 SC 687 (SC)

Greater rights comprise of several lesser rights. When the greater right is the admitted ‘object of transfer’, no treatment may be extended to lesser rights that also get transferred along with the transfer (of greater rights) because these lesser rights were not the ‘object of transfer’. And where the greater right is excluded from the treatment in GST, then all lesser rights avail the same exclusion as they are not vivisected.

Example (330): Absolute title to land includes right to use, right to license, right to develop, etc. and the right to alienate one or all of those rights. Sale of land (greater right) being absolute, right to lease (lesser right) is also transferred.

Example (331): Ownership of shares in a company includes right to attend and vote in shareholder’s meeting, right to dividend and even right to pledge those shares or transfer them entirely. Ownership of shares (greater right) subsumes all other rights as shareholder (lesser rights) and transfer of lesser rights cannot give rise to any tax treatment independent of that which the transfer of greater right attracts.

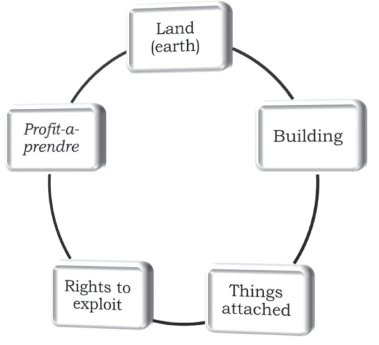

2.7 Profit-a-prendre

French law uses this expression profit-a-prendre, which means right of ‘taking away’ that a determinate person or an indeterminate group of persons enjoy.

Example (332): Right to draw water from a river or lake or well. Example (333): Right to catch fish in a river or lake.

Example (334): Right of passage through the field of another.

Profit-a-prendre is much more than easement (discussed later) where easements include profit-a-prendre. And profit-a-prendre that is not included in easement would be ‘profit-a-prendre in gross’ which does not exist independent of a dominant heritage (discussed later). Right to take away is NOT easement under Easements Act. Easement is all the dominant rights over another’s immovable property and where profit-a-prendre bears the indicia of an easement, then those would be included as easement.

“A profit-a-prendre is a right to remove and appropriate any part of the soil belonging to another, or anything growing upon or attached to the soil or the purpose of the profit to be gained from the property thereby acquired, that is, for example, a right to take gravel, stone, trees and so forth.”

– Saiyad Wajid Ali Shah v. Umrai Bibi (1904) 1ALJ 621.

Lease is an intangible immovable property where ‘possessory rights’ are transferred by creating an ‘interest’ in the immovable property in favour of the Lessee to the exclusion of even the Lessor (discussed later). The ‘form’ of an arrangement may be a lease but the terms of lease permit Lessee to ‘take away’ the harvest of the land only to return land per se at the end of term is not lease but lease to enable ‘taking away’ or profit-a-prendre.

“It has long been settled that an agreement for the sale and purchase of growing grass, growing timber or underwood, or growing fruit, not made with a view to the immediate severance and removal from the soil and delivery as chattels to the purchaser, is a contract for the sale of an interest in law.”

– Mahabir Prasad v. Enayat Ilahi AIR 1951 All 608.

And where the contract is ‘with a view to’ permit taking away of produce of the land – fruit or ore – is a contract for sale of chattel as chattel. Recollect the opening statement that tree is a warehouse of fruits on it, ready for harvest.

“Only the lease of the forest wood is given to you.

In a lease, one enjoys the property but has no right to take it away. In a profit a prendre one has a licence to enter on the land, not for the purpose of enjoying it, but for removing something from it, namely, a part of the produce of the soil.”

Shantabai v. State of Bombay AIR 1958 SC 532.

Profit-a-prendre is the right to take away and not the chattel taken away. Profit-a-prendre in gross is the right of taking away that is inextricably connected with land (dominant heritage). This right of taking away (before anything is taken away) is intangible immovable property that can lawfully be transferred, and the Transferee does the ‘taking away’. Where Transferee is permitted to take away chattel in present, then it is a contract for sale of goods, but whether Transferee is permitted to take away chatte of the future, it is the right that is transferred since the chattel is not yet in existence.

2.8 Land, a specie

Land, therefore, is NOT the whole of the discussion about immovable property. There are many different ‘immovable properties’ in question and land is just one of them. To equate paragraph 5, Schedule III to Central GST Act to every specie of immovable property, whether tangible or intangible, would be an attempt at expanding the words of said Schedule III.

Example (335): A planet does not make up the entire universe. Universe is made of billions of stars, planets and other heavenly bodies. Stars emit their own light and planets reflect light of others. Each has its own characteristic and are different from each other. Planet is not the whole of the universe.

And expanding the words of said Schedule III would be to eliminate the differences between the various species of immovable property that exist in one person to the exclusion of all others. Immovable property is not limited to tangible immovable property and contains vast number of ‘rights’ that are less than ‘title’ but which procure lawful enjoyment akin to ownership. Immovable property is a universe of things and land or building are just two of the many things that make up this universe. It includes rights to exploit the benefits inherent which is intangible immovable property and the very special right to ‘taking away’ that which the land (earth) has produced (current yield) and is yet to produce (future yield).

2.9 Registration

Immovable property, whether tangible or intangible, is void if it is conveyed without a registered written instrument. Registration does not itself assure title. Registration is a record of title. Unregistered record is no record. Ver- bal contracts are permitted and in certain laws customary gifts like Hiba is even recognized. But where non-testamentary instrument conveys interest, right or title, registration is sine qua non (discussed later).

Asserting existence of rights demand production of registered written record. Absence of such a record raises presumption against person asserting title to property. Lease for a period of more than one (1) year is void unless in writing and duly registered (see section 107). This is the reason for the popular practice of have eleven (11) month lease arrangements that are not written or written but not stamped and registered.

2.10 Movable property

Without a definition in this Act, reference to General Clauses Act and Registration Act are inevitable:

| General Clauses Act | Registration Act |

| Section 3(36) “Movable Property” shall mean property of every description, except immovable property; | Section 2(9) “Movable Property” includes standing timber, growing crops and grass, fruit upon and juice in trees, and property of every other description, except immovable property; |

For these reasons, determination of ‘object of transfer’ is essential to ensure movable property do not get treatment as immovable property and vice versa. And based on principle traceable to Marshall v. Green between these two definitions, common misconceptions are also cleared.

Example (336): Electricity is movable property.

Example (337): Human blood is movable property.

Example (338): Air is movable property.

Example (339): Goodwill is movable property.

Example (340): Brand name is movable property.

Example (341): Software is movable property.

Example (342): Pets are movable property.

Example (343): Livestock are movable property.

Unless ‘proprietary rights’ can be exercised over the object, being ‘movable’ alone will not be sufficient to qualify as movable property.

Example (344): Wildlife are not movable property.

Example (345): Leasehold rights are not movable property.

Example (346): Building is not movable property.

All property are covered by these two definitions. And if it is not property then it is not movable property, even if it is movable. To be property, it must bear all the attributes of a right qua the thing. Contract of sale is not property, but the goods delivered pursuant to that contract are property. Expenditure incurred to acquire a thing does not necessarily make that thing a property, movable or immovable. Unless rights exist, it would NOT be property.

Example (347): Pre-paid expense is not property.

Example (348): Insurance policy is not property.

Example (349): Personal club membership is not property.

Example (350): Crypto-currency is not property.

Example (351): Non-fungible tokens are not property.

Merely because a market exists does not make the thing a property. And absence of a market does not deny existence of property. Rights are con- trasted as chose-in-possession and chose-in-action. Former is stock-on-hand and latter is holder of endorsed bill of lading (authorizing to collect the property). Mere right to sue is not chose-in-action. Right to the property that becomes available when successful in suit makes the right a choice-in-action and property in every sense. And where the property is movable, this right is also movable property. Rights are broader than property. Property is the sub-set and rights form the superset. Rights must be enforceable otherwise they will not be property (see examples provided earlier). Rights become vested when conditions to their vesting are satisfied. And vesting conditions on failure (to be satisfied) operate as divesting conditions. And until they become vested, they are inchoate (information). Vested rights that are property enjoy the protection afforded by Constitution against unlawful deprivation in article 300A.

2.11 Actionable claim

Beneficial interest in movable property that is not yet in existence is ‘actionable’ in a Court of law. And a claim admissible in an ‘action’ in a Court of law is ‘actionable claim’. Sections 3 and 130 address actionable claims in this Act.

Example (352): Lottery-ticket is actionable claim.

Example (353): Bills receivable is actionable claim.

Example (354): Accrued rent is actionable claim.

Example (355): Accepted insurance claim is actionable claim.

Disclaimer: The content/information published on the website is only for general information of the user and shall not be construed as legal advice. While the Taxmann has exercised reasonable efforts to ensure the veracity of information/content published, Taxmann shall be under no liability in any manner whatsoever for incorrect information, if any.

Taxmann Publications has a dedicated in-house Research & Editorial Team. This team consists of a team of Chartered Accountants, Company Secretaries, and Lawyers. This team works under the guidance and supervision of editor-in-chief Mr Rakesh Bhargava.

The Research and Editorial Team is responsible for developing reliable and accurate content for the readers. The team follows the six-sigma approach to achieve the benchmark of zero error in its publications and research platforms. The team ensures that the following publication guidelines are thoroughly followed while developing the content:

- The statutory material is obtained only from the authorized and reliable sources

- All the latest developments in the judicial and legislative fields are covered

- Prepare the analytical write-ups on current, controversial, and important issues to help the readers to understand the concept and its implications

- Every content published by Taxmann is complete, accurate and lucid

- All evidence-based statements are supported with proper reference to Section, Circular No., Notification No. or citations

- The golden rules of grammar, style and consistency are thoroughly followed

- Font and size that’s easy to read and remain consistent across all imprint and digital publications are applied

CA | CS | CMA

CA | CS | CMA